Monday, July 14th, 2025

Luxury’s new balancing act: from inhouse production to strategic externalization

Luxury brands are shifting from full integration to hybrid models, balancing in-house production for core, heritage items with strategic externalization for scalability, speed, and flexibility. Today, 65–70% of luxury production is outsourced. Externalization is no longer low-cost outsourcing, but high-value partnerships with specialized manufacturers, often in nearshoring hubs like Albania and Turkey, enabling faster delivery, lower structural costs, and access to innovation. A new collaborative and consolidated ecosystem is emerging, where brands, suppliers, and investors co-develop resilient supply networks—preserving artisanal heritage while adapting to a fast-changing global landscape.

When vertical integration becomes a burden

In the past decade, luxury brands heavily invested in vertical integration to secure quality, preserve artisanal heritage, and ensure traceability, especially in key manufacturing hubs like Italy. Owning suppliers offered control, but by 2024 this model began to show its limits.

As brands grew larger and more complex, internalization led to rising costs, organizational rigidity, and slower response to market shifts. The fixed burden of in-house production clashed with the industry’s growing need for agility and financial flexibility. This turning point marked the beginning of a new phase: strategic externalization.

Externalization: partnering for agility and innovation

Luxury companies are now adopting a more nuanced approach to production, called strategic externalization, or partnering with specialized third-party manufacturers. Industry estimates suggest that 65–70% of total luxury product volume is managed through externalized production model. Rather than doing everything in-house, brands are identifying which activities truly need to be internal (for creativity, secrecy, or heritage reasons) and which can be entrusted to expert suppliers without diluting the brand’s value. The key is that today’s external partnerships are not the anonymous outsourcing of old; they are often deep collaborations with high-caliber producers that may work across multiple luxury labels.

This new model of externalization is exemplified by the rise of consolidated supplier platforms in the luxury sector. Private equity investors have been busy building large multi-brand manufacturing hubs, essentially aggregating the best of Italy’s artisans under corporate groups that can serve many clients. A notable example is Gruppo Florence, founded in 2020, which has rapidly acquired small manufacturers (leather goods makers, shoemakers, knitwear producers, etc.) to create a one-stop Italian supply platform serving top luxury clients, currently made of 37 companies, 1,000 professionals in product development and industrialization and a network of +1000 subcontractors.

This illustrates how external suppliers themselves are evolving: they are bigger, better capitalized, and highly specialized, often with backing from investment funds that see opportunity in making the luxury supply chain more efficient.

For luxury brands, partnering with these specialized third-party producers offers several advantages:

- Agility and speed: external manufacturers that serve multiple brands have to stay on the cutting edge of production techniques and timing. They can often deliver innovation faster by leveraging cross-industry learnings or scaling new technologies that an individual brand’s in-house facility might not adopt as quickly. A supplier working with a dozen luxury clients gains a broad view of emerging trends and can diffuse those innovations rapidly. In an externalization model, a brand can tap into this broader innovative ecosystem without bearing the full R&D cost alone.

- Flexibility and scalability: working with outside suppliers turns a portion of fixed costs into variable costs. Instead of running a factory year-round, a brand can ramp orders up or down with a partner as market demand dictates. This is especially valuable in the current climate of uncertainty. The agility to adjust volumes and product mix quickly helps luxury companies respond to seasonal swings or unexpected spikes in demand. Additionally, if one supplier faces a bottleneck, brands can multi-source across the network, a practice that purely insular operations cannot easily replicate.

- Lower structural costs: brands save on capital expenditures and ongoing overhead, since the burden of investing in new machinery, expanding facilities, or hiring and training additional labor falls on the supplier (who spreads those costs over multiple clients). Luxury houses, in turn, improve cash flow and financial efficiency by not tying up capital in production assets. This leaner model was attractive even before 2020, but after the pandemic and in an inflationary environment, the cost relief is even more important.

Crucially, the stigma once associated with “outsourcing” is fading in the luxury industry. It’s no longer about chasing the cheapest needlework in a far-flung location at the expense of quality. Now, it’s about finding the best partner for the job, whether that partner is an hour down the road in Tuscany or across the Mediterranean. As one industry leader put it, the goal is to “strengthen the sectors of excellence” by working with those who have the specialized skills, rather than doing everything solo.

In many cases, externalization means engaging the same artisans or technicians who would have been acquired in an internalization model, but keeping them in a more entrepreneurial setting where they can serve multiple brands. This can spur innovation, as these producers are exposed to diverse design teams and challenges, driving them to continuously elevate their craft.

“Made In” vs “Made Out”: evolving geography of Luxury production

Underpinning this strategic shift is a reassessment of the age-old question: where should luxury goods be made?

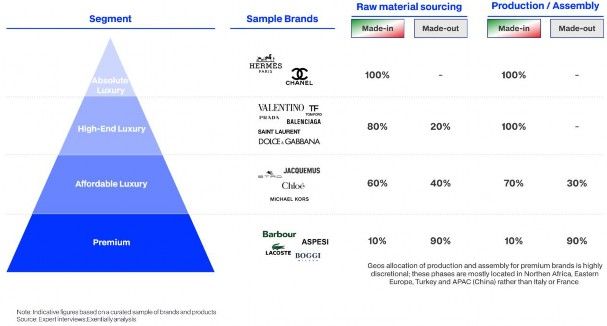

The cachet of a “Made in” label (Italy or France, or Switzerland, depending on the product) remains immensely important for top-tier luxury brands. This origin signifies quality, tradition, and often justifies the high price tag. Luxury maisons still fiercely protect local production of their most iconic, high-value items. For example, nearly all Hermès bags are made in France; top Italian leather goods and couture houses similarly pride themselves on being hand-made domestically. As noted, High-End and Absolute luxury segments source as much as 80–100% of its production in Italy for categories like leather goods, footwear, and ready-to-wear, with only a small remainder perhaps in other parts of Western Europe. Even as externalization rises, maintaining a “Made in” pedigree for flagship products is non-negotiable for true luxury.

However, the industry is becoming more pragmatic about when “Made in” matters most.

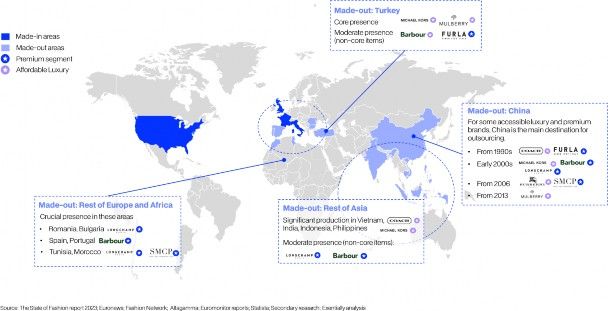

In product categories or brand segments where heritage and exclusivity are slightly less critical, often the lower range of luxury or premium brands just below the top tier, companies are increasingly open about “Made out” strategies, meaning production outside the traditional luxury-manufacturing countries. The last two decades saw a lot of premium fashion production move to Asia (China in particular) in search of cost savings, but the new “Made out” is no longer synonymous only with Asia.

Operational efficiency is the driving force: brands that compete on a lower price point or higher volume need the cost advantages of external production, and they are finding them closer to home as well as abroad.

Italian brands are quietly leveraging Albania’s skilled yet affordable workforce to produce certain garments or components, then finishing or assembling products in Italy to ensure quality and—where compliance conditions allow—apply the final “Made in Italy” stamp.

This trend has accelerated further due to mounting instability along traditional shipping routes, including Houthi rebel attacks in the Red Sea and rising piracy in the Gulf of Aden. As these threats disrupt global maritime logistics and inflate lead times, nearshoring to Mediterranean and Eastern European countries like Albania or Turkey has become a strategic choice to mitigate risk, reduce transit delays, and preserve responsiveness in luxury supply chains.

Crucially, this diversification of production geography is about balancing heritage and efficiency.

Luxury brands are segmenting their product lines: core, heritage pieces tend to stay “Made in”, preserving that aura of exclusivity, while more routine products (like an entry-level accessory, a fabric sneaker, or a seasonal ready-to-wear piece) might be made in Portugal, Turkey, or Asia without harming the brand image. Premium brands, which don’t compete purely on elite craftsmanship, go even further, often producing the bulk of their collections in cost-effective countries.

The stigma of “Made in China” in luxury has reduced somewhat (especially as Chinese manufacturing quality has improved), but brands are still mindful of consumer perceptions. Hence the pivot to “Made in Europe (but not Italy)” for a middle ground: places like Portugal or Eastern Europe can offer a semi-“European made” cachet at lower cost.

It’s also worth noting that geopolitical and logistical considerations drive this evolving “Made out” strategy. The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent supply chain crises highlighted the risks of over-reliance on distant factories. Shipping delays, tariffs, and geopolitical tensions have made far-flung sourcing less appealing for time-sensitive luxury fashion. Thus, even cost-conscious brands are hedging by keeping production closer.

The result is a more distributed manufacturing footprint for the industry: high-end luxury clinging to its local roots, while the broader premium market optimizes globally, but increasingly with a regional bias (e.g., Europe and the Mediterranean for European brands).

Collaboration in a consolidating supply ecosystem

While externalization gains momentum, the luxury supply chain is also undergoing a parallel shift: consolidation. In recent years, many small, high-end suppliers, especially in Italy, have been absorbed by leading brands or investor-backed platforms. This trend responds to two pressures, both to preserve endangered craftsmanship and scale critical capabilities in a more structured, resilient way.

Luxury groups like Chanel, LVMH, Prada, and Zegna have acquired dozens of artisanal manufacturers (tanneries, knitwear producers, textile mills) not only to secure materials and talent, but also to improve traceability, reduce lead times, and co-develop innovations. Many of these deals include capital expenditures to modernize equipment, boost automation, and ensure compliance with rising sustainability standards. Crucially, preserving heritage remains a core motivation: ownership helps keep artisanal know-how rooted in Italy and aligned with brand values.

New industrial platforms are emerging, bringing together dozens of high-end Italian manufacturers under a single corporate structure and offering premium production at scale. At the same time, a new collaborative mindset is taking shape across the entire luxury supply chain. Competitors like Prada and Zegna, or Chanel and Brunello Cucinelli, have started co-investing in suppliers to share risk and ensure continuity. In 2023, for example, Chanel and Cucinelli each acquired a 24.5% stake in Lanificio Cariaggi, with the Cariaggi family retaining 51%, signaling a shared commitment to safeguarding excellence in Italian textile manufacturing.

In this evolving landscape, the line between internal and external grows thinner. What emerges is a networked ecosystem, built on alignment more than ownership, where brands, suppliers, and investors collaborate to deliver excellence, resilience and innovation.

A hybrid path forward

The luxury industry in 2025 finds itself charting a hybrid path between insourcing and outsourcing, blending the best of both models. The earlier era of aggressive insourcing was about safeguarding what makes luxury unique (quality, heritage, exclusivity) and that priority remains. However, the recent pivot toward externalization recognizes that in a rapidly changing, globalized market, nimbleness is key.

The emerging strategy is to internalize what is core and differentiating, while externalizing what is peripheral or scale-driven. By doing so, luxury brands aim to stay true to their DNA (through tightly controlled in-house craftsmanship for signature products) while leveraging external partners for speed, efficiency and fresh ideas in other areas.

In many cases, the decision to internalize or outsource also hinges on product type:

- Carry-over items (continuative pieces, iconic products), especially those with high margins or strategic relevance, tend to be managed in-house. However, when volumes exceed internal production capacity, these too can be outsourced.

- Seasonal collections, being time-sensitive and less recurring, are more frequently externalized to specialized partners that can flex capacity and respond to fast-changing demand.

While seasonal items dominate SKU rotation in apparel, carry-over plays a structurally greater role in bags and footwear, accounting for ~80% of revenues in bags and ~50% in shoes.

In embracing this trend, luxury companies are effectively lightening their load. They become less asset-heavy, more financially flexible, and can redirect investment to areas like digital innovation, customer experience, or sustainability initiatives, all crucial for future growth.

Importantly, this shift does not mean a loss of quality or authenticity. On the contrary, by working closely with fewer, larger, and more advanced suppliers (often still located in traditional craft regions), brands can uphold their standards. The difference is that the relationship is more collaborative and less ownership-driven. In a sense, the luxury sector is moving toward the kind of “networked organization” model seen in other industries: a strong central brand orchestrating a constellation of partners.

The “Made in” vs “Made out” dichotomy will continue to evolve as well. We can expect luxury houses to increasingly communicate not just where an item is made, but how it is made, highlighting artisanal craftsmanship and sustainable practices wherever they occur. The emphasis on traceability and authenticity means that even externalized production must meet the luxury bar for excellence and transparency.

In the end, the customer cares that the product is of superb quality and aligns with the brand’s ethos; how the brand achieved that (through owned ateliers or partnered factories) is becoming an internal strategic choice more than a marketing point.

In conclusion, luxury industry is recalibrating its supply chain for the next era. The pendulum swing toward internalization has moderated, giving way to a more flexible model that cherishes heritage but embraces external expertise. By striking this balance, luxury brands aim to have the best of both worlds: absolute control where it counts, and agility and efficiency where it matters.

This emerging trend positions the luxury sector to weather economic uncertainties and fast-moving trends, all while continuing to deliver the exceptional products and experiences that define luxury. In a world of constant change, the ultimate luxury for brands may well be the agility to change gracefully without betraying their core identity.